When you type "king" into a chatbot and it somehow knows you're thinking about "queen", it's not magic. It's embeddings. These aren't just numbers-they're the hidden language of how AI understands meaning. Every word, sentence, or idea you throw at a large language model gets turned into a long list of numbers. That list? That's an embedding. And it’s how machines start to "feel" language the way humans do.

What Exactly Is an Embedding?

An embedding is a vector-a sequence of numbers-that captures meaning. For example, the word "apple" might become a vector like [0.8, -0.2, 0.6, 0.1, ...] with 384 or 768 numbers in it. You can’t read it like a sentence. But the computer doesn’t need to. What matters is where that vector sits in space.

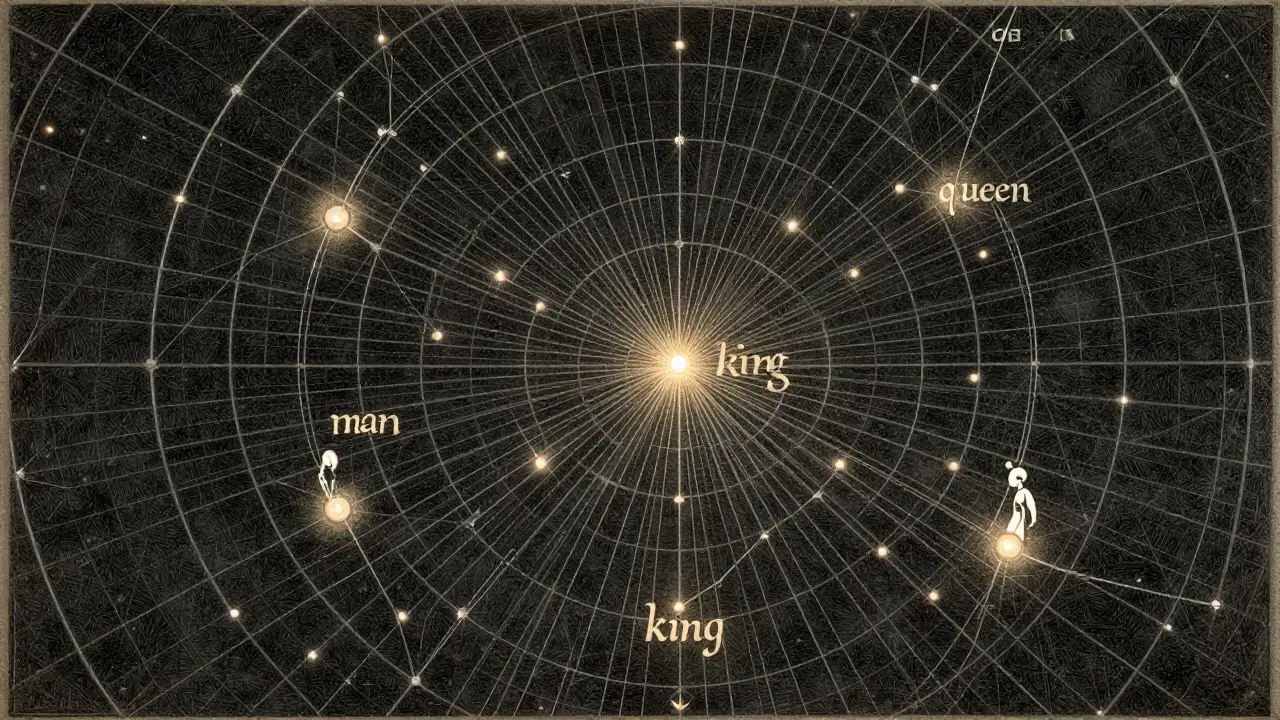

Think of it like a map. On a real map, cities that are culturally or geographically close are near each other. In embedding space, "dog" and "cat" are close. "Car" and "truck" are neighbors. But "dog" and "quantum physics"? Far apart. The distance between vectors isn’t random-it reflects how similar the meanings are. This is why you can do math with words. If you take the vector for "king," subtract "man," and add "woman," you get something close to "queen." That’s not luck. It’s the structure of meaning baked into the numbers.

Static vs. Contextual Embeddings: The Big Shift

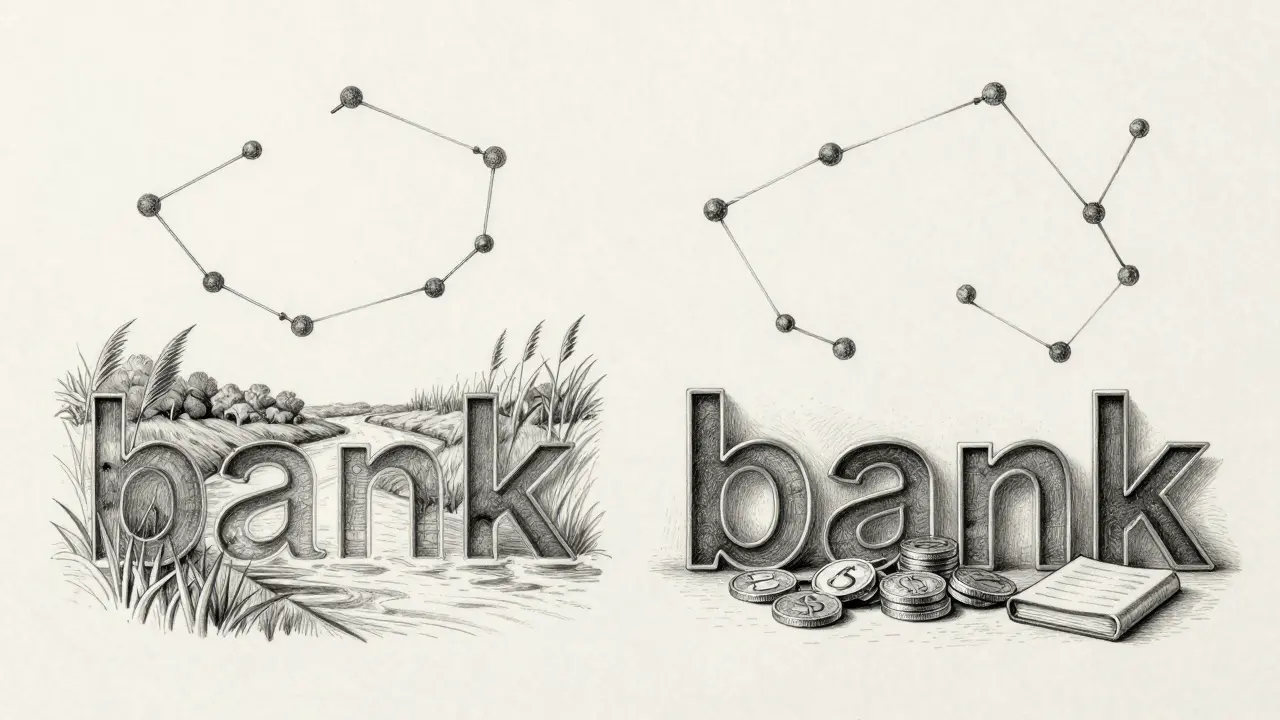

Early models like Word2Vec and GloVe treated words like fixed labels. The word "bank" always had the same vector, whether you meant "river bank" or "money bank." That caused problems. If you asked a model about "bank" in a sentence like "I deposited money at the bank," it had no idea you weren’t talking about a river.

That changed with BERT in 2018. BERT and modern LLMs like GPT don’t assign one vector per word. They build vectors based on the whole sentence. So "bank" in "river bank" gets a different embedding than "bank" in "ATM bank." The model looks at every word around it-before and after-and adjusts the vector accordingly. This is called contextualization. It’s why today’s models handle ambiguity, sarcasm, and complex grammar so much better.

How does it work? Each word passes through multiple layers of neural networks. At each layer, it gets refined-its meaning adjusted based on what came before and what’s coming next. By the end, the vector isn’t just about the word. It’s about the word in this context. That’s why sentence transformers like Sentence-BERT became popular. They’re trained specifically to compare whole sentences, not just single words. They cut the time to compare 10,000 sentences from hours to seconds.

How Big Is the Vector? Why Dimensionality Matters

Embedding vectors aren’t all the same size. Some have 384 numbers. Others have 1,024 or even 1,536. Why the difference?

Think of dimensionality like detail in a photo. A 384-dimensional vector is like a 720p image-clear enough for most tasks. A 1,536-dimensional vector is 4K. More dimensions mean more room to capture subtle differences. But more dimensions also mean more memory, more processing, and slower responses.

Here’s what’s common today:

- Word2Vec: 300 dimensions (good for basic word relationships)

- GloVe: 50-300 dimensions (used in early search systems)

- BERT-base: 768 dimensions (standard for most enterprise use)

- Google’s Vertex AI: up to 1,024 dimensions

- Amazon Titan: 1,536 dimensions (for high-precision tasks)

For most applications-chatbots, search, recommendations-768 dimensions hits the sweet spot. Too low, and you lose nuance. Too high, and you waste resources. Companies like IBM and JPMorgan Chase found that jumping from 384 to 768 improved accuracy by 12% on legal document search, but going beyond 1,024 gave almost no extra gain.

Where Are Embeddings Used? Real-World Impact

Embeddings aren’t just theory. They’re powering real systems right now.

- Enterprise search: 92% of companies now use vector embeddings to power internal search. Instead of typing keywords, you type a question like "What’s the policy on remote work?" and the system finds the most similar document-even if it doesn’t use the exact same words.

- Recommendations: Amazon’s product recommendations use embeddings to find items that "feel" similar. A customer who buys a DSLR camera might see recommendations for tripods, lenses, or editing software-not because they’re tagged that way, but because their embeddings are close in vector space.

- Healthcare: Mayo Clinic uses embeddings to help doctors search medical records. A query like "symptoms of early-stage diabetes" pulls up patient notes, research papers, and treatment guides-even if they use different terminology.

- Fraud detection: JPMorgan Chase built a system that compares transaction patterns using embeddings. It flags unusual behavior by spotting vectors that don’t fit the normal pattern, reducing false positives by 18%.

These aren’t experiments. They’re production systems. The vector database market is projected to hit $2.8 billion by 2027. Why? Because embeddings turned search from keyword matching into meaning matching.

Limitations: Where Embeddings Fall Short

Embeddings aren’t perfect. They have blind spots.

First, they struggle with rare words. If a medical term like "pulmonary embolism" only appears a few times in training data, its embedding might be weak. Studies show performance drops 15-20% on specialized legal or medical texts compared to general ones.

Second, they don’t handle logic well. "Not good" and "bad" should be similar, right? But embedding models often keep them apart. Why? Because they learn from patterns in text, not rules. If "not good" always appears with "not" and "bad" never does, the model treats them as different.

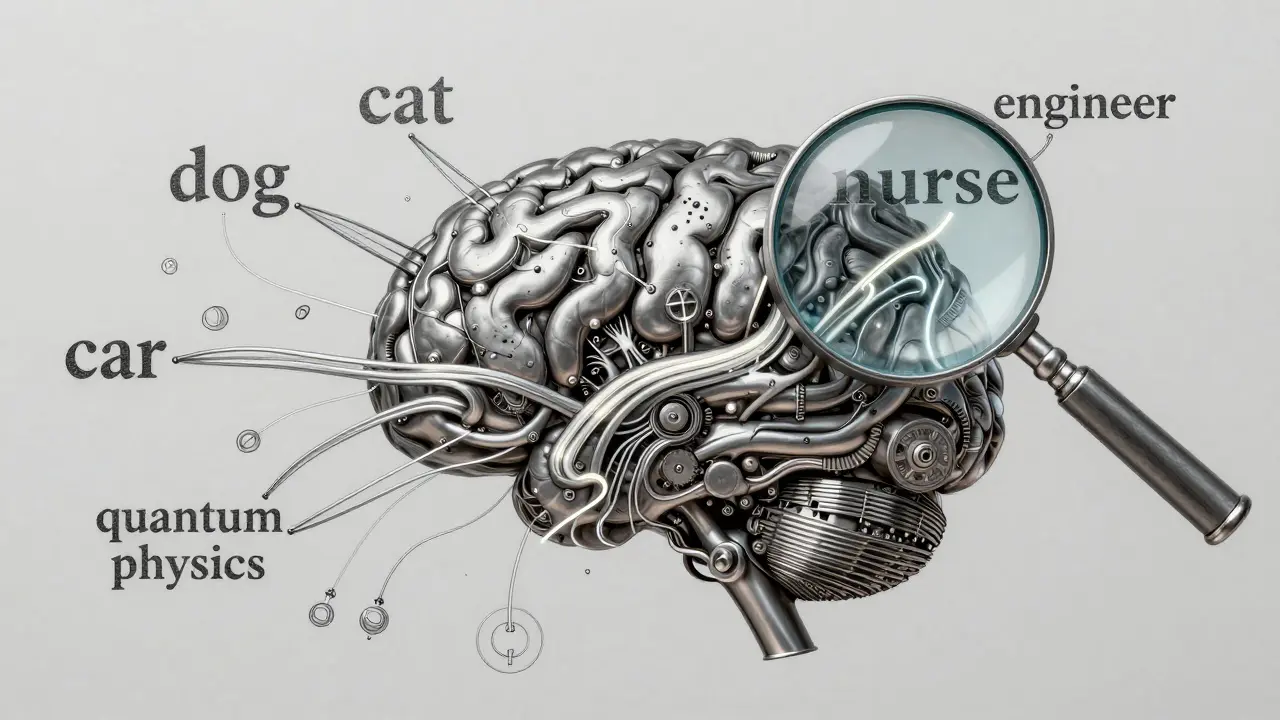

Third, embeddings inherit bias. If the training data mostly links "nurse" with "female" and "engineer" with "male," the vectors reflect that. Studies using the Word Embedding Association Test (WEAT) show gender bias scores as high as 0.65 on standard models. That’s not a bug-it’s a feature of how they’re trained.

And then there’s computation. Generating a single embedding with BERT-base takes about 0.5 GFLOPS per token. That’s not much for one word. But for a 10,000-word document? That’s 5,000 GFLOPS. You need a powerful GPU. Many startups fail because they underestimate the cost of running embeddings at scale.

What’s Next? The Future of Embeddings

Researchers aren’t standing still. New breakthroughs are coming fast.

- Sparse embeddings: Google’s 2025 research showed embeddings can be compressed by 75% without losing meaning. Instead of 768 numbers, you use 192-with 95% of the accuracy. That slashes memory use and speeds up search.

- Multi-modal embeddings: Meta’s ImageBind model now creates a single vector space for text, images, and audio. You can search for "a cat sleeping in sunlight" and find matching photos, even if the image has no text.

- Quantization: Converting 32-bit floating-point vectors to 8-bit integers cuts storage by 80% with less than 2% accuracy loss. This makes embeddings viable on phones and edge devices.

- Dynamic embeddings: Google’s 2026 roadmap explores embeddings that change as users interact. Your search for "best budget laptop" today might shift the vector for "budget" based on your past clicks, making future results more personal.

And beyond that? DeepMind’s 2025 whitepaper suggests embeddings might one day mimic how human brains store meaning-grouping concepts by association, not just proximity. That could lead to models that understand not just what you say, but what you mean.

Best Practices for Using Embeddings

If you’re building something with embeddings, here’s what works:

- Use cosine similarity, not Euclidean distance. Cosine measures direction, not distance. Two vectors pointing the same way-even if one is longer-are similar. That’s perfect for meaning. It boosts accuracy by 12% on semantic tasks.

- Normalize your vectors. If you skip this, your comparisons break. Always scale vectors to unit length before comparing.

- Use domain-specific fine-tuning. A general-purpose embedding won’t cut it for legal or medical text. Fine-tune on your data. IBM’s team saw a 22% boost in accuracy after training on internal documents.

- Watch out for out-of-vocabulary words. If a word wasn’t in training, the model guesses. That can drop accuracy by 25-30%. Use subword tokenization (like Byte Pair Encoding) to handle rare terms.

- Test with real queries. Don’t just rely on benchmark scores. Try your own questions. If the top result doesn’t make sense, your embedding isn’t tuned right.

Embeddings turned AI from pattern-matchers into meaning-makers. They’re not the whole story-but they’re the foundation. Without them, LLMs would just be fancy autocomplete engines. With them? They start to understand.

What’s the difference between embeddings and traditional keyword search?

Traditional keyword search looks for exact word matches. If you search for "how to fix a leaky faucet," it returns documents containing those exact words. Embeddings understand meaning. They’ll return results about "repairing a dripping pipe" or "fixing water pressure in the kitchen sink," even if none of those words appear in your query. It’s like searching by intent, not by dictionary.

Can embeddings work with languages other than English?

Yes, but not equally well. Multilingual embeddings like those from Sentence-Transformers can map meanings across languages. For example, the vector for "dog" in English is close to the vector for "perro" in Spanish. But performance drops for low-resource languages with less training data. Models trained on English-heavy datasets often struggle with Swahili, Urdu, or Quechua. Cross-lingual embeddings are improving-Meta’s 2025 models hit 90%+ accuracy on zero-shot translation-but they still lag behind English performance.

Do I need a GPU to use embeddings?

Not always. For small-scale use-like a personal app or prototype-you can run lightweight models (like all-MiniLM-L6-v2) on a CPU. But for production systems handling thousands of queries per second, a GPU is essential. BERT-base needs 410MB of GPU memory per model instance. Cloud APIs (like AWS Titan or Google Vertex AI) handle this for you, so you don’t need your own hardware.

Why do embeddings sometimes give weird results?

They’re trained on data, not logic. If your training data has more examples of "CEO" paired with "he" than "she," the embedding will reflect that bias. Or if a word appears in very different contexts (like "apple" as fruit vs. company), the model might average those meanings into a weak, unclear vector. Also, if you use the wrong similarity metric or forget to normalize vectors, results get noisy. Always validate with real examples.

How do I know which embedding model to choose?

Start with your use case. For simple word similarity, use Word2Vec or GloVe. For sentences or paragraphs, use Sentence-BERT or all-MiniLM-L6-v2. For enterprise search or RAG, go with BERT-base (768 dimensions) or Amazon Titan (1,536). Test on your own data. A model that scores high on public benchmarks might fail on your documents. Always run a small pilot before scaling.