When a large language model gives you an answer in Spanish, Hindi, or Swahili, how sure should you be that it’s right? If the model says it’s 95% confident, is it actually correct 95% of the time? In English, we’ve started to answer this question. But for most other languages, the answer is: we don’t know - and the model is probably lying to you.

Why Confidence Scores Lie in Non-English Languages

Large language models are trained mostly on English data. Even the ones that claim to support 100 languages? They still think in English. When you ask them a question in Arabic or Portuguese, they often translate it internally, answer in English, then translate back. That process adds noise. And the model doesn’t realize it’s making more mistakes. So it overconfidently says things like, "I am 98% sure this translation is perfect," when in reality, it got the grammar wrong, missed cultural context, or mixed up idioms. This isn’t just a minor flaw. In healthcare, legal, or financial applications - where people rely on LLMs to summarize medical records or draft contracts in their native language - this overconfidence can lead to serious harm. Studies show that LLMs are significantly less accurate in non-English languages. But their confidence scores? They stay just as high. That mismatch is the problem. The model doesn’t know it’s struggling. And if we don’t fix that, we’re building systems that feel trustworthy but are quietly unreliable.What Calibration Actually Means

Calibration isn’t about making the model smarter. It’s about making its confidence match reality. Think of it like a weather app. If it says there’s a 70% chance of rain, and it rains 7 out of 10 times when it says that - that’s calibrated. If it says 70% but it only rains 2 out of 10 times? That’s not calibrated. The model is lying about its certainty. For LLMs, calibration means: when the model says it’s 80% confident in an answer, it should be right about 80% of the time - no matter if the question is in English, French, or Vietnamese. Right now, that’s rarely true outside English. The goal isn’t to make every answer correct. It’s to make the model say, "I’m only 40% sure," when it’s genuinely unsure. That’s useful. It lets humans step in. It prevents blind trust.Four Methods That Work - But Only in English

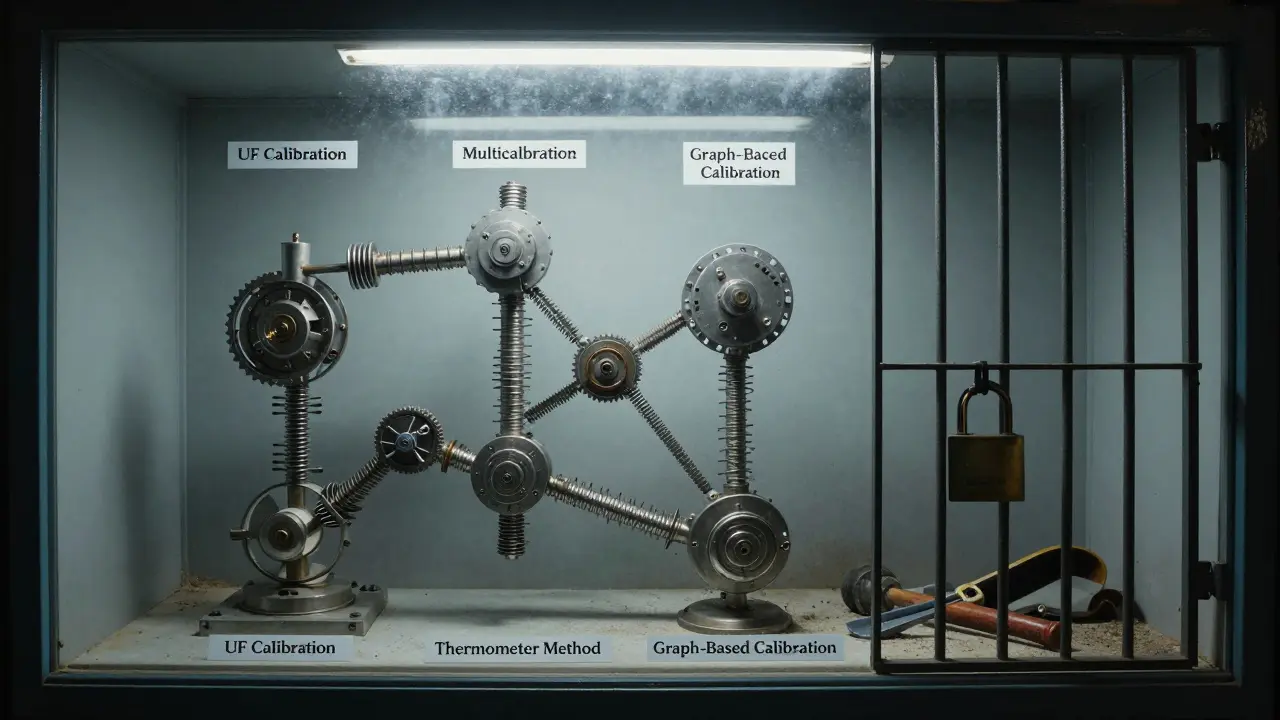

There are four main techniques researchers are using to fix this - and they all work well in English. But almost no one has tested them in other languages.- UF Calibration: This method splits confidence into two parts: "Uncertainty" (how confused the model is about the question) and "Fidelity" (how well the answer matches what it should say). It only needs 2-3 extra model calls. It’s simple. It works. But all tests were done on English datasets like MMLU and GSM8K. Nothing in Spanish, Chinese, or Bengali.

- Multicalibration: Instead of looking at confidence globally, this method checks it across groups - like age, gender, or topic. The smart part? It could group by language. But no one has done it. The paper mentions it as a possibility, but doesn’t test it. That’s a missed opportunity.

- Thermometer Method: This one uses a simple temperature scale. Too hot? The model’s too confident. Cool it down. It’s like adjusting oven heat. Easy to plug in. But it assumes the model’s errors are evenly distributed. They’re not. In low-resource languages, errors cluster in specific patterns - like verb conjugations or honorifics - that temperature scaling can’t catch.

- Graph-Based Calibration: This one generates 5-10 different answers to the same question, then builds a map of how similar they are. If all answers agree, it’s probably right. If they’re all over the place? The model’s guessing. It’s clever. But again - tested only on English. What happens when the same question in Tagalog produces five wildly different translations because the model doesn’t know regional dialects? The graph might still show high agreement, because the model is consistently wrong in the same way.

The Real Gap: No One’s Testing This in Non-English Contexts

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: every paper on LLM confidence calibration published in 2024 used English datasets. Not because it’s easier - but because no one bothered to try otherwise. We know LLMs perform worse in non-English languages. We know they’re overconfident. We know the consequences can be severe. Yet the research community hasn’t connected the dots. Imagine a doctor in Brazil using an LLM to summarize a patient’s medical history in Portuguese. The model says, "I am 97% confident this diagnosis is correct." But it misread a symptom because the term "dor lombar" was confused with "dor nas costas" - two different pain types. The doctor trusts the model. The patient gets the wrong treatment. That’s not hypothetical. It’s already happening. And no calibration method has been tested to prevent it. The tools exist. The techniques are proven - in English. We just need to apply them where they’re needed most: in languages that aren’t English.What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for researchers to catch up. Here’s how to handle non-English LLM outputs right now:- Never trust confidence scores in non-English responses. Treat them as noise, not signal.

- Ask for multiple answers. Generate 3-5 responses to the same question. If they contradict each other, the model is guessing. Don’t pick the one with the highest confidence score - pick the one that makes the most sense to a native speaker.

- Use human validation. If the output matters - legal, medical, customer service - have a fluent speaker review it. No algorithm replaces that.

- Build your own calibration. If you’re using an LLM in Spanish, create a small test set of 100 questions with known correct answers. Run the model. Track how often it’s right when it says "90% confident." Adjust your own confidence thresholds based on real results.

The Future: Calibration Must Be Language-Aware

The next big leap in LLM reliability won’t come from bigger models. It’ll come from models that understand their own limits - in every language they claim to support. We need calibration methods that:- Group responses by language family, not just topic

- Use low-resource language data to train confidence predictors

- Recognize when errors are systemic (like missing tone in Mandarin) versus random

- Adapt calibration based on dialect, formality, or regional usage